Summer is just around the corner, so it’s time to stop thinking about red wines for a few months and begin to savor whites and rosés.

Given the explosion of sales of red Rioja it can be easy to overlook what’s happening with white and especially, rosé. In the short time since Inside Rioja last explored rosé in Rioja, a lot has happened.

At that time I wrote:

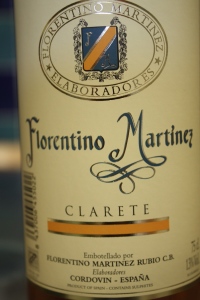

Rioja actually produces two styles of pink wines: rosado and clarete. At first glance, the difference is merely color, with rosado a medium reddish pink and clarete a very pale orange.

At the end of the article was a comment about some possible changes:

I was also surprised to see a bottle of Muga rosé with a much paler pink color than in the past. Maybe clarete or at least pale orange-tinted rosés have an international future.

Benchmarks-the old (Mateus rosé from Portugal) and the new (Pure from Provence)

There have indeed been changes here, but first, let’s review how pink wines in Rioja have traditionally been made. One style, called rosado, is vinified with tempranillo and/or garnacha with skins in contact with the juice for a few hours to extract color but no skin contact during fermentation. The other is clarete, where both red and white grapes are fermented with the skins, producing a very pale pink wine. The regulations of the Rioja DOC require that at least 25% of a clarete blend must be made from red grape varieties so a clarete could have as much as 75% of white grapes.

Originally, claretes were made mainly in the upper valley of the Najerilla river in Rioja Alta around the villages of San Asensio, Cordovin, Badarán, Azofra and Alesanco. This style has become so popular in northern Spain that clarete lovers just ask for “un Cordovin”. The area around the Najerilla valley celebrates its relationship with clarete by organizing a ‘Batalla del clarete’ that takes place on a Sunday in the second half of July in San Asensio.

A clarete from Bodegas Ontañón (Photo: Tom Perry)

Today we can say that pale orange tinted rosés and clarete are gaining in popularity both in Spain and internationally. Probably the first sign of change came as a consequence of the increase in worldwide sales of rosés from Provence with their characteristic pale pink color.

Sales of Provence rosé (Source: Wine Market Review based on statistics from French Customs)

Rioja wineries wanted to take advantage of this increase in demand for very pale rosés but were forbidden from doing so because the Rioja Regulatory Board defined rosé as having higher color intensity. It took some time before wineries were able to get the definition changed. Today, the rule for the minimum color intensity of a Rioja rosé is .1UA/cm, measured as the sum of A420+A520+A620. This allows very pale rosés to be made.

For the non-tech minded, basically it’s using photospectrometry to measure the wine’s capacity to absorb light at three wave levels: 420, 520 and 620 nanometers. A lighter intensity will have a lower number and vice-versa. For example, in Rioja, the minimum color intensity for a red is 3.5 UA.

Now, Rioja rosés are available from very pale pink to light red to meet demand in different markets. Some wineries like CVNE and Barón de Ley make more than one style.

(Photo: Tom Perry)

There’s a huge range of rosados and clarets from Rioja in the marketplace. Try a pale rosé, a clarete and a darker-hued rosé. I’m sure you’ll love the comparison!